FRAMING – Romanticizing Worldviews

Framing – Romanticizing Own Worldviews

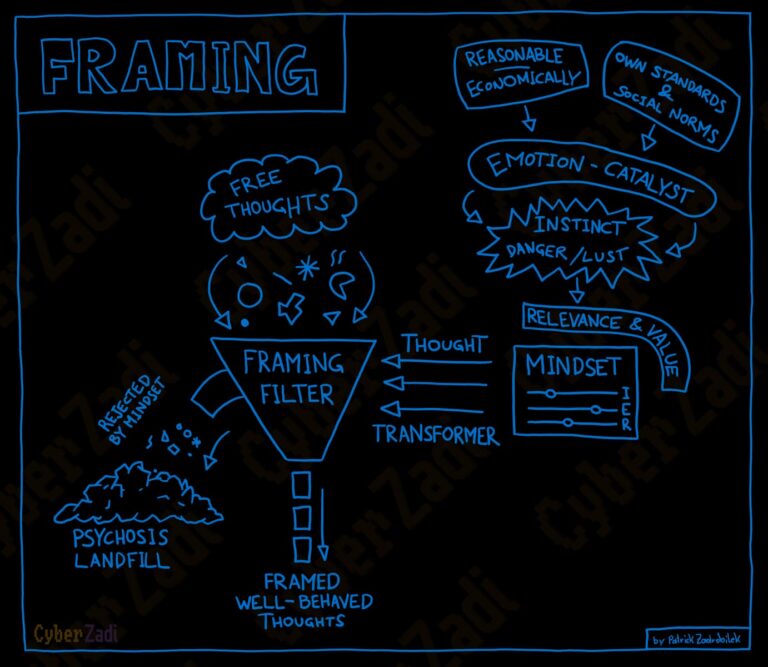

Framing is the personal “contextualization”, hence the framework through which we classify and interpret perceptions and thoughts. It shapes our worldview and our understanding of how everything within it operates, determining how freely we can move or when we hit our boundaries. Framing acts as a filter, reducing perceived and stored “raw thoughts” to essentials and focusing on the values defined within the framing. It defines our stance on various issues that hold particular significance for us. This could encompass perspectives on morality, health, money, dangers, objects, people, or ideologies. These values are primarily shaped by childhood influences but also by daily needs activated by intrinsic and extrinsic incentives. Often, the values within our framing strongly correlate with associated emotions. The greater the values, the more restrictive the framing through which we interpret things.

Framing is part of our mindset and is largely responsible for our behavior.

Influencing Systems

► Risk Assessment (Need for Security)

The instinctive perception of threats combined with learned perceived dangers and the urge to either confront (fight) or avoid (flight) them shapes our risk assessment. Every perception and resulting thoughts are given a risk assessment. When we assign a high-risk value to a thought, fear emotions develop. This linking of thought with a risk value and fear emotions defines our framing – how we see and interpret that thought from our risk-assessment perspective.

► Self-image from Ego + Self-Confidence

Our self-image is also shaped by framing, with the critical mind acting as a counterbalance and questioning the meaningfulness of the framing. The effectiveness of this process depends on whether our ego (our motivational energy) is sufficiently large but not overly so, and whether our self-confidence is not too small in relation to it. Only with strong self-confidence are we able to recognize our own framing and question it with our critical mind. If our ego is too dominant and disproportionately large compared to our self-confidence, our subconscious will do everything (biases, fallacies, excessive needs) to protect our framing and our worldview.

► Value System within Framing

From birth, every thought has a certain value that defines our framing based on associated emotions and needs. These values shape morality and steer mental focus and motivation through visualization of incentives.

📜 Read the CyberZadi Article: Value System – Emotional Currency

► Emotions

➼ Values are reinforced or diminished by emotions

The strength of instinctive feelings (danger vs. desire) defines the strength of emotional relations and thus the value of a perception or thought construct, forming corresponding expectations. Influenced by self-image (the ego) coupled with self-confidence – provided it is already present (developing in childhood), expectations generate corresponding needs in various need categories.

Mainly through external (and also internal) sanctions and the resulting fears, we engage in commitments with the sanctioner (our self-image) to avoid negative emotions. This, in turn, links perceived emotions with the values of these perceptions.

Initially, our values are established in early childhood and refined and expanded throughout life by highly formative situations and experiences. The precision and precise definition of values hold greater importance than expanding values, which is naturally more challenging as it requires significant character changes (framing changes).

Dynamic Framing System

However, framing should not be seen as absolute and unchangeable. Instead, it is a dynamic system that determines how our subconscious mind deals with and interprets our abstract raw thoughts. It is the part of the mind that carries our beliefs and metaphorical commitments. Here, stimuli from incentives or sanctions are linked with corresponding expectations and strong emotions, creating value perceptions.

Experiences from early childhood, through formative authorities such as parents, teachers, and similar, shape the framework of actions and thoughts through their personal rules and regularities, and provide meaning through corresponding incentives and matching arguments. These form corresponding need-triggers that we will repeatedly respond to later in life.

Whenever our mind consciously or subconsciously recognizes new connections that represent a significant emotional value, the framing is adjusted. This can “narrow” the framing, limiting previously open views, usually through sanctioning contexts and general fears. Alternatively, it can expand the framing and present completely new perspectives to the mind. This slightly loosens the framing, and the mind learns to learn like a child, which was allowed to think much more freely—at least until it received too many prohibitions and commands.

Situation-Specific Framing

Framing, or a “focused” and temporarily narrower view of things, occurs in many situations. These include:

• Adaptive framing in the presence of specific people (sympathy effect, social conformity, …)

• Adaptive framing in specific locations

• Modified framing through emotions (grief, euphoria, fear, etc.)

• Restricted framing during activities under intense focus (flow)

• Focused framing due to dominant needs

• Distorted framing through cognitive biases and prejudices (bias)

• Distorted framing through acute instinct influence (danger/reward)

• Short-term framing expansion through vision and resulting incentive (reward-sanction prospect)

➼ and, of course, combinations or variations of them

Questioning Framing

Now, what is the most efficient method to keep framing dynamic and not let it restrict us, but ideally see it as a guideline or orientation, not as fixed blinders influenced too strongly by our emotions and learned risks?

It’s quite simple: by questioning our own values.

Whenever we feel that a stimulus raises more questions for us than we can answer ourselves, we are called upon to pursue this stimulus and gather further information before our mind forms an opinion. Because this opinion can quickly arise from various cognitive biases and fallacies that our subconscious interprets through the framing in a preconceived, established manner.

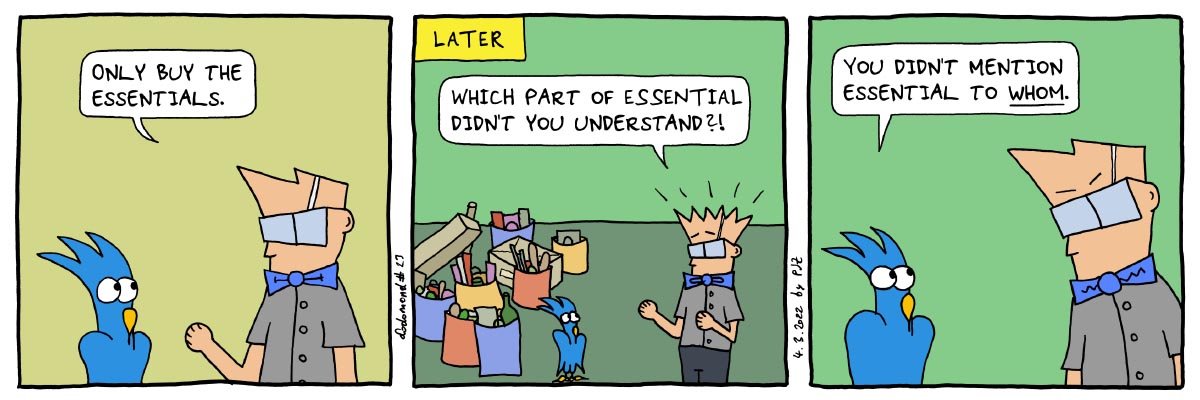

The first question would be: “Did this perspective, opinion, or view originate from a personal experience of mine, or was it trained into us through external suggestion in the form of a narrative? For example, did someone tell us about it? The essential aspect of narratives is that we were not present in the situation being narrated, and therefore, the narrative is not part of our experiences. The deceptive aspect of narratives is that they can be so convincing that we remember them as if we experienced them ourselves. Thus, narratives from naturally accepted authorities can exert great persuasive power on us and shape us accordingly. Red flags here include repeated repetitions, fear in various forms, and generally incentives such as the threat of sanctions or the prospect of rewards that appeal to our subconscious.

Point Of View and New Perspectives

The own identity is constantly evolving – it’s just a matter of whether we are aware of it or not. New perspectives, new views, reframing are expansions of or consciousness. Our personal view of things gives us a sense of security and defines our personal identity. So, how do we deal with perspectives that don’t fit into our thinking pattern, that lie outside our bubble, or possibly shake our worldview?

It often happens during a conversation when we hear another person’s viewpoint and think to ourselves, “If you put it in this way…”. As soon as we say this sentence, we have opened our consciousness, allowed empathy – we have changed our perspective and are now considering a topic from a different point of view – a perspective we have not previously explored. In this way, we expand our consciousness and new paths open up for our identity, new ways of thinking that lead to new dimensions of thought. Suddenly, we recognize things that we were previously blind to because they were not visible with our previous perspective – they were not within our mental field of view.

So, what prevents us from changing perspectives? Why is it so difficult to expand or framing? Ironically, it is often the fear of giving up our own identity. We assign strong values to our personality aspects. These values are created through our experiences and the “efforts” we put into dealing with these experiences that form our framing. This apparent security of our opinion makes them seem very valuable. This attribution of value prevents us from accepting new perspectives because they would question the value of our existing frames – we perceive that as a direct attack on our identity, our personality, our so secure and fixed views.

Purposeful Framing

Perspectives are highly personal; they shape who we are and how we interpret our worldview. It becomes challenging for our personality when framing hinders our growth, leading us to believe we don’t need to learn anything new because we already know everything necessary.

Our parents imprint our initial framing by molding us in their image and imparting their view of the world onto us. In our teenage years, we may realize that these initial perspectives often don’t align with how we personally experience situations. The crucial question is how deeply rooted our existing values are, which shape our framing and sets our viewpoints. When we realize that some values don’t make much sense for our lives and we allow these values to change, our framing shifts and we see things from new perspectives. As long as we allow ourselves to question our own values by becoming aware of new values, we are also able to change the framing, expand it and adopt different perspectives.

Questioning the meaningfulness of existing values in relevant life situations demonstrates a person’s maturity and is not a sign of indecision or uncertainty. It’s permissible to doubt our own views and their attributions of value frequently. This keeps the mind fresh and open to new perspectives, more rational approaches, and a more pleasant mutual understanding – leading to a happier, stress-free life. And most importantly, it bolsters self-confidence and curbs ego!

I look forward to lively and open discussions and shared experiences in the comments!

✎ Patrick

Book List

📙 Influence – Robert Cialdini

Topics: Automatisms in general, group cohesion, social proof, compliance – compliance

📙 Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

Topics: The different areas of the brain and the methods of processing information

📙 Reframe Your Brain – Scott Adams

Topics: Strategies and techniques for altering your mental framing to improve your thinking, overcome challenges, and achieve personal success.

Affiliate Links

Deutsch

Deutsch